ELR/BPA - CHaMP Grand Ronde Crew Variability Study

Project Type: Sponsored Research Project Sponsor: Eco Logical Research, Inc. Project Location: Grand Ronde River, Oregon Status: Complete

Project Overview

Purpose of Project

This project sought to quantify the magnitude and effect of observer variability when using total station surveys to characterize stream topography. Specifically, we were interested in whether or not crew variability limits the quality of the data, the calculation of of DEM-derived habitat metrics (e.g. water depth), and the ability to reliably make inter-comparisons between different sties and/or changes through time at one site (i.e. time series geomorphic change detection analysis).

Abstract

The goal of the Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program (CHaMP) is to implement a standardized fish habitat monitoring program in watersheds with Endangered Species Act (ESA)-listed steelhead and Chinook populations of the Interior Columbia River Basin. The CHaMP protocol is comprised of methods that capture topographic, substrate, riparian vegetation, large woody debris, and fish cover in spatially balanced locations within each watershed. Streambed and floodplain topography (including surveying channel unit boundaries) is surveyed using total stations affording the derivation of high spatial resolution (i.e. 10 cm) DEMs and water depth maps of each sample site. DEMs are used to monitor changes in physical habitat and calculate spatially explicit geomorphic changes through time.

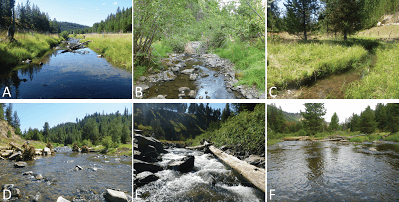

In the summer of 2011 the CHaMP program concluded its pilot field season where crews from 8 agencies and organizations sampled 338 unique sites in 10 sub-watersheds of the Columbia River Basin. Like any monitoring campaign that will rely on different crews, either between years or among sites, there are underlying questions regarding whether calculated differences between repeat surveys are real or due to noise from discrepancies in how or what the different crews sampled. To discern the magnitude and effect of crew variability in topographic total station surveys a study was conducted in August of 2011. Seven crews (Columbia Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, Eco-Logical Research, Inc., Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife John Day , Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Upper Grande Ronde, Quantitative Consultants, Inc., Tetra Tech, and Terraqua) sampled the same six stream reaches in the Upper Grande Ronde River basin of northeast Oregon over a time period we can be sure no significant geomorphic changes occurred. The six sample reaches selected included 3 smaller tributary sites and 3 larger mainstem sites.

**Figure 1. ** Site photos of the CHaMP crew variability study sites including the three tributary sites: Fly Creek (A), Spring Creek (B), West Chicken Creek (C) and the three mainstem Grande Ronde River sites: upper (D), middle (E), and lower (F).

We sought to answer the following questions:

1. What is the magnitude of inter-crew variability when multiple crews visit the same site?

2. Are large magnitude discrepancies among crews due to systematic surveying and post-processing errors or simply due to a lack of sampling effort?

3. To what extent does crew variability affect:

a. the precision of DEM-derived metrics such as mean water depth, bankfull width, and water sinuosity?

b. the precision of detecting geomorphic changes to physical habitat?

Significance of Project

- This study is significant to monitoring programs that use high precision topographic surveying techniques and rely on different crews among sites and across years.

- This project identified protocol adjustments, training improvements and enhanced QA/QC measures to minimize systematic errors and reduce crew variability that CHaMP integrated into their 2012 protocol (CHaMP, 2012).

Methods

Survey Methods:

- Crews surveyed reach topography with total stations and followed the CHaMP protocol (Bouwes et al., 2011) topographically stratified sampling method which includes collecting both XYZ points and breaklines.

- Crews were the first in a line of QA/QC checks and were responsible for editing their point data, breaklines, and TINs to ensure that derived DEMs were an accurate representation of what they saw in the field.

- In addition to surveying topography, crews collect auxiliary habitat metrics, including: habitat unit type, invertebrate drift, substrate, canopy cover, riparian vegetation, large woody debris and pool tail fines.

Analysis Methods:

- Raster maximum-minimum analysis to quantify the full range of DEM elevation and DEM-derived water depth variability across all crews at each site.

- Spatially variable estimate of DEM uncertainty using a 2 input Fuzzy Inference System (FIS) developed by Wheaton et al. (2010) based on point density (a proxy for sampling) and surface slope (a proxy for topographic complexity).

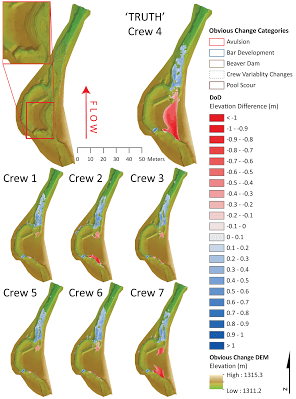

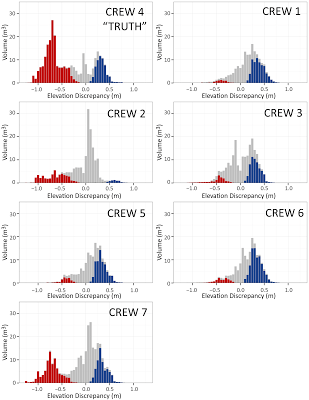

- Modeled potential geomorphic change scenarios using Geomorphic Change Detection (GCD) software. Of the many metrics CHaMP data can be used to estimate, geomorphic change detection is potentially one of the most sensitive to crew variability and the quality of the topographic data. As this is only the first year of data collection in CHaMP, repeat topographic surveys were not available that captured ‘real’ geomorphic change. As such, we created an artificial DEM that represented a plausible future state of the channel. An ‘obvious’ change scenario was modeled whereby a beaver built a dam between Time 1 and 2 with a subsequent flood resulting in channel avulsion. We hypothesized that all crews should be able to detect this change, regardless of crew variability because the magnitude of the signal exceeded likely DEM uncertainties. Each individual crew’s DEM was used as Time 1. The ODFWUGR DEM was selected as truth and used to model potential change (i.e. Time 2 surface).

Results

Survey & Processing Errors:

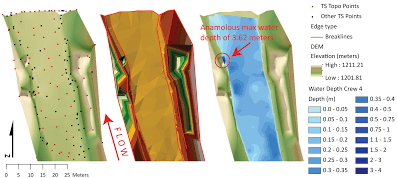

- Most common errors were TIN busts not caught by crews when editing TINs. These were typically associated with incorrect rod heights.

- Most observed errors are easy to fix post-hoc (e.g. TIN bust). Some are difficult or nearly impossible to remedy post-hoc and could compromise an entire survey (e.g. excessive error in a backsight check).

- All observed errors are easy to avoid with clear guidance and training.

**Figure 2. **Example of a systematic survey error by Crew 4 at the Grande Ronde River upper site. Here, we inferred that while collecting Topo coded points, the crew incorrectly recorded the total station rod height (left). This led to several large magnitude TIN busts (middle) that were not caught by the crew during the TIN editing process. One of the river-left busts fell within the wetted channel and resulted in a localized anomalous 3.62 meter water depth (right) in the derived water depth maps where all other crews had detected a maximum water depth on the order of 0.60 m.

####Range of Variability & Surface Quality:

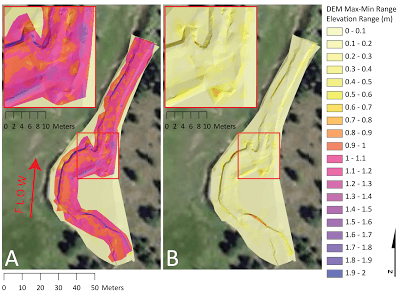

- In most instances, the full range of variability among crews was within estimates of DEM uncertainty for total station surveys.

- Variability was least in the wetted channel (i.e. the primary fish habitat) and worse on the channel margins and floodplain.

- FIS should be calibrated for lower point density surveys and adjusted to account for breaklines.

**Figure 3. **Fly Creek DEM maximum-minimum difference with (A) and without Crew 2 (B) who made a systematic survey error by adding 1 meter to the recorded total station instrument height.

**Table 1. ** Results of DEM maximum-minimum difference analysis (i.e. full range of variability across crews) and 2 input FIS elevation uncertainty raster output.

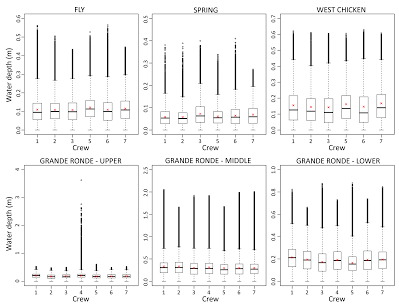

Effect of Crew Variability on DEM-derived Water Depth Rasters:

- At the 3 tributary sites, average water depths varied by up to 3 cm while maximum water depth varied by 14 cm. At the mainstem sites, average water depths varied by up to 4 cm while the maximum water depth varied by up to 3.14 m. Depth frequency distributions indicate crews measured comparable variations in depth throughout the surveyed reaches.

**Figure 4. ** Water depth distributions for each crew grouped by site. Boxplots represent interquartile range (IQR; bottom quartile (25%), median and upper quartile (75%)), whiskers are at a maximum of 1.5 IQR, and circles represent outliers greater than 1.5 IQR. Means are represented with a red x.

Ability to Detect ‘Obvious’ Geomorphic Change:

- All crews missed the ‘true’ net degradational signal as a result of not having a large enough survey extent that extended onto the active floodplain

- Within the wetted channel all crews accurately captured both the beaver dam construction and deposition of avulsed material on a downstream mid-channel bar

- Crews need better guidance on survey extents required to detect large scale changes such as channel avulsion

**Figure 5. **Results of modeled ‘obvious’ geomorphic changes of Time 2 (i.e. scenario DEM) - Time 1 (i.e. each crew’s 2011 DEM). DEMs of difference (DoDs) are on the left and the gross volumetric elevation difference distributions calculated form the DoD are on the right. Here Crew 4 represented ‘true’ change. Areas in blue represent deposition while areas in red represent erosion.

Conclusions

- Crews collected topographic data of sufficient quality and consistency that their DEMs and water depths show the same basic spatial patterns. Additional guidance on point densities and breakline data collection could help promote higher qualities and consistency.

- The majority of large magnitude discrepancies among crews were attributed to a systematic error by one crew (different crews across sites). Most systematic errors are easy to identify and fix post-hoc in the data editing or QA/QC process (e.g. TIN busts). These errors are also easy to avoid with more targeted training and QA/QC procedures.

- Survey extent matters, particularly with long term datasets, and can affect our ability to accurately capture geomorphic change. The topographic data among crews was of adequate quality to support geomorphic change detection. However, crews were not given adequate guidance on how far to extend their survey boundaries and how to identify areas that the channel could plausibly migrate into. These floodplain areas can generally be surveyed with minimal effort to facilitate a more accurate portrayal of future geomorphic changes.

Related Links & Research

- ELR/BPA: ISEMP Lemhi Topographic and Aerial Photographic Methodological Intercomparison

- Integrated Status & Effectiveness Monitoring Program

- Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program

- CHAMP - Bridge Creek Sites

- \2012. CHaMP (Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program). Scientific protocol for salmonid habitat surveys within the Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program, Prepared by the Integrated Status and Effectiveness Monitoring Program and published by Terraqua, Inc., Wauconda, WA, 188 pp.

- \2011. Bouwes N, Moberg J, Weber N, Bouwes B, Bennett S, Beasley C, Jordan CE, Nelle P, Polino S, Rentmeester S, Semmens B, Volk C, Ward MB and White J. Scientific Protocol for Salmonid Habitat Surveys within the Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program, Prepared by the Integrated Status and Effectiveness Monitoring Program and published by Terraqua, Inc., Wauconda, WA, 118 pp.

Project Outputs

Presentations from this Project

- \2011. Bangen SG, Wheaton J and Bouwes N. A Methodological Intercomparison of Topographic and Aerial Photographic Habitat Survey Techniques, AGU Fall Meeting 2011. American Geophysical Union: San Francisco, CA, pp. EP41A-0573.

- \2011. Portugal E, Bangen SG and Wheaton J. The Relative Importance of Inserting TIN Topographic Breaklines in DEM Creation, AGU Fall Meeting 2011. American Geophysical Union: San Francisco, CA, pp. H51I-1312.

- \2011. Wheaton JM and Bangen SG. Crew Variability in Topographic Data, Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program Post Pilot Season Workshop. NOAA: Portland, OR.

- \2011. Wheaton JM, Bangen SG and Portugal E. Topographic Survey Comparisons, Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program Post Pilot Season Workshop. NOAA: Portland, OR.**

Publications from this Project

- Bangen SG*, Wheaton JM, Bouwes N, Jordan C, Volk C and Ward M. 2014 Crew variability in topographic surveys for monitoring wadeable streams: a case study from the Columbia River Basin. Earth Surface Processes and Land Forms. DOI: 10.1002/esp.3600.

- \2013. Bangen SG. Comparison of topographic surveying techniques. MS Thesis. Utah State University, 168 pp.

- \2012. Bangen SG and Wheaton JM. CHaMP Crew Variability: Influence on Topographic Surfaces & Derived Metrics, Report to Eco Logical Research, Inc. and the Columbia Habitat Monitoring Program, Logan, Utah, 79 pp.

- \2011. Ward MB, Nelle P and Walker SM (Eds). CHaMP: 2011 Pilot Year Lessons Learned Project Synthesis Report. Bonneville Power Administration: Portland, OR, 95 pp.

Datasets from this Project

- All data used in this study available on champmonitoring.org

Project Details

Project PI: Joseph Wheaton Project Personnel from ET-AL: Sara Bangen (MS Student) Project Collaborators: Nick Bouwes (ELR), Chris Jordan (NOAA), Carol Volk (South Fork Research), Kelly Whitehead (South Fork Research), and Philip Bailey (North Arrow Research) Funding Source: Bonneville Power Authority - Sub-award to USU from Eco Logical Research, Inc. Project Start Date: **September 2011 **Project End Date: November 2013